All photographs courtesy of Rahr.

A fascinating project happened right under my nose, and I almost missed it. Last year I was talking to a brewer—for the life of me I can’t recall who it was—who casually mentioned pFriem’s “fancy new pilsner malt.” I am a malt enthusiast and like to think I keep up on these matters—especially with breweries who sponsor this blog, and yet I hadn’t gotten wind of it. That brewer was right, though: pFriem spent months working with Rahr to create a pilsner malt that has now been released for general sale. This is cool for a whole bunch of reasons, but in particular, it marks an evolution in American brewing. It was created to meet the needs of a craft brewery that wanted not just efficiency, but character; a malt that can work in a flagship pilsner or an IPA.

“I hear so many people who are really passionate that they’re using Idaho Pils now—that’s a Great Western product. I don’t think that malt would have been so exciting, even three to five years ago, for breweries to drop that name like it’s a big deal.”

For the better part of a century, suppliers have been focused on the needs of domestic lager producers. That changed on the hops side of the equation, as brewers started to seek something very different for their IPAs. The same breweries who today demand not just Citra, but precise lots of Citra, haven’t always been as picky with their malt. That’s not true in other countries, where breweries have narrow preferences about their malts, and sometimes even the barley variety. This new project is one piece of evidence that American brewers are now getting pickier about their malts, too. It’s a very cool development.

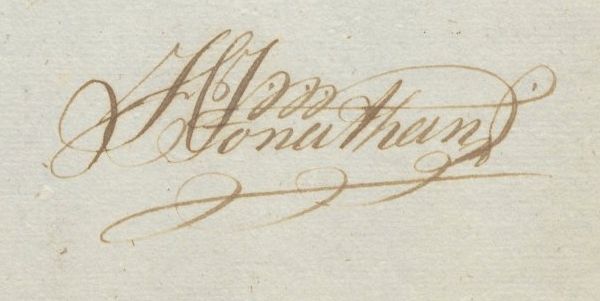

I wasn’t surprised when I learned that pFriem was behind this project. Their Director of Brewery Operations, Campbell Morrissy, has a PhD in barley breeding and genetics from Oregon State, a degree he completed while working at pFriem. If anyone was going to bring a sophisticated sense of a brewery’s needs to a maltster, Campbell seemed like the guy to do it. It gave me a perfect opportunity to delve into my malt enthusiasm and learn more about what kind of malt pFriem would want and how that differed from what was available. Barley and malt are also a bit impenetrable scientifically—at least to layman like me—and I used this opportunity to learn more about it. Learning how the new Rahr pilsner malt was developed became an education in some of those sciencey issues. So let’s meet the new malt, called To Thee, and learn how it came to be.

The Year that Went Wrong

I knew pFriem was having some issues with their malt. I actually witnessed it directly. I was a judge on medal round of pilsners at the Oregon Beer Awards in 2023. The three previous years pFriem had taken gold. When we learned who took gold that year—a small brewpub in Corvallis—and that pFriem hadn’t even medaled, it caused a bit of a stir. I talked to co-founder Josh pFriem about it last year and he mentioned that something had gone wrong with their regular pilsner malt, creating what amounted to an existential crisis at a brewery where half the production is Pilsner. (They were back to gold in 2024 and took silver last year.)

Campbell picked up the story when I interviewed him and Rahr’s Matt Letki for this article. “We joke that the whole brewhouse is optimized to make pilsner,” he said. “So if we start seeing issues with our Pilsner, we know we have a problem. It’s not a one-off: Pilsner should be the same all the time. But we were struggling analytically and sensorily; we were having issues with yield, issues with haze—and we were having issues around DMS as the driver of our sensory problems.”

pFriem wasn’t sure what to do next. They spoke with their regular supplier and began to audit others for a potential replacement. They had just about settled on a different supplier when the brewery started talking to Rahr about creating a bespoke malt that would precisely meet their needs. If Campbell was a beer guy who spoke malt, Matt Letki, who has a degree in brewing and worked as a commercial brewer before moving into malt, was sort of his inverse—a malt guy who spoke beer. Matt recalled the conversation. “I said to Campbell, ‘Don’t be bound by what you think we can do, tell me what you want.”

pFriem wanted several things. “What we were looking for was a more restrained enzyme package,” Campbell said. During Covid, they installed an impressive GEA brewhouse from Germany and their beer was drying out too much. “We could not keep attenuation on Pils—or anything—in control” because of the brewhouse efficiency and the high enzyme load. Beer that should have been finishing out at 1.8 or 1.9 Plato was going down to 1.4 or 1.5. As a stopgap, they were able to address that in the brewhouse. Ideally, they wanted a lower-enzyme malt.

Campbell on Free Amino Acid (FAN) “You need amino acids for a healthy fermentation profile. But all that stuff floating around in your beer that's no longer valuable for yeast is just prone to oxidation. It's going to start converting into off flavors—various aldehyde production pathways that create everything from [flavors of] sherry to toffee to cooked potato and other savory notes.”

They also wanted was a malt with lower free amino nitrogen. “North American barley varieties have been bred for high free amino nitrogen, and malthouses have been accustomed to providing that for adjunct brewers,” Campbell explained. “However, in all-malt, and just generally in our process, we don't need that much FAN, and anything we leave behind is only going to create a less palatable beer.”

Finally, pFriem regularly blends their malts, using some deeper-colored Weyermann pils, so they needed a very light-colored pilsner malt. The problem with very pale malts is that they contain a precursor for the off-flavor dimethyl sulfide, or DMS. “So looking for less of those DMS precursors, which is the challenge of being low color and low DMS. You know, the way to get rid of DMS is heat it. So kiln it a little longer, drive it off.” That, of course, darkens the color.

When Matt challenged pFriem to tell him what they needed in a malt, they gave him a riddle: how do you get a malt with two characteristics that are inversely proportional to each other?

Barley and Process

In the brewhouse, riddles like this often come down to process and ingredients. Matt and the folks at Rahr took a very similar approach. Rahr decided to address this partly by choosing a particular barley variety, and partly by choosing a malthouse with certain special advantages.

They started with raw ingredients. “We needed to look at a barley variety that, while it would modify well and produce low beta-glucans, it would not overmodify the protein and create a very high free amino nitrogen,” he explained. With the right barley, they could get part of the way there, and a promising new variety called Churchill seemed to have what they were looking for. Agronomically, it’s very robust, which means growers will be excited to plant it. For the brewer, it’s also excellent, as Matt described: “It does give really good beta-glucan modification, or breakdown. If you modify it well, it tends to throw a little bit lower solubilized protein, and it tends to throw a little bit of a lower free amino nitrogen. And, where it's growing, agronomically, it also tends to be a little bit lower overall protein.”

The second piece of the puzzle was Rahr’s Canadian malthouse in Alix, Alberta. (Rahr started life as a Wisconsin brewery, expanded into malting, and after Prohibition, set up a malthouse in Shakopee, MN, near Minneapolis. They now operate the two facilities in the US and Canada.) The town of Alix is located in the dry prairies of Alberta at about 3,000 feet (900 meters) elevation. Those two facts make it possible for Rahr to kiln their malt more gently.

Barley varieties.

“The higher you go in altitude, the lower the boiling temperature of water,” Matt said. “If you have a very low moisture going into that final kilning stage [because of the naturally dry climate], you're not gonna produce the same amount of color. So because water boils at a lower temperature at higher elevation, in Alix, the malt dries more quickly. We've got this kind of, this really nice combination of high altitude, the right barley variety, the right malting process; everything kind of coming together to really make this malt.”

In the Brewhouse

It’s no surprise that pFriem is very pleased with To Thee. In partnering with a malthouse, they have created a malt suited perfectly to their needs. Campbell, the barley and malting expert, mentions that that’s how it has always been. “If you look back to some of the historic places in brewing, Germany, the UK, [brewing and malting] aren’t separate. And honestly AB has a malthouse, Coors has a malthouse. But in the craft industry, we’ve really focused on the brewery. The suppliers supply us stuff. But brewing truly starts in the field.”

It was a big commitment from Rahr, though. Rahr won’t be able to make a specific malt for every brewery. They’re hoping that by meeting the needs pFriem had, they would be serving the larger craft market. So far the reviews have been positive. To Thee is new enough that not a lot of brewers have had a chance to use it, but I tracked down a few who have:

Gavin Lord, who used to hold Campbell Morrissy’s job at pFriem, has used it at his Portland brewery. “To Thee has quickly become a staple for Hetty Alice. I’ve noticed over the years that the nuances between pilsner malts are often overlooked. To Thee is just a very versatile, high quality grain. It’s rich without being too sweet, it’s complex yet subtle, and it performs beautifully in traditional lagers or modern hop-forward ales alike. I’m a fan.”

Mat Sandoval at Living Haus (also Portland): “The To Thee malt from Rahr is a great new addition to our team’s tool chest. The soft bread-dough qualities of this malt work well in our delicate lagers while also providing enough of a backbone for our highly hopped IPAs.”

And in Scottsdale, AZ, Goldwater’s Shawn Turner: “We have loved using Rahr To Thee. It has become an extremely versatile ‘Swiss Army knife’ for us. It allows us to create anything from clean, crisp West Coast IPAs to robust beers with excellent mouthfeel. The light color makes it incredibly adaptable, and its drinkability is impressive even when it stands alone in our light lager. The low color and sweetness levels also provide a perfect foundation to showcase our hop-forward beers.”

Since the craft era dawned, American brewing has been characterized by hops. That’s not likely to change. But even when the focus is largely on the flavors and aromas of one ingredient, the others have an important role to play. Several years back, we entered a new phase of brewing in which breweries started to focus on how malts would accent their hoppy ales. With the slow development of lagers as an important component of craft brewing, appropriate malt is even more relevant. This is another one of those watershed moments that mark and industry leveling up. To Thee is one of the first large-scale North American malts specifically designed for the craft industry. If it’s a hit, it won’t be the last.

One of the mysteries of brewing that’s always fascinated me lies in this question: is the way a malt smells and tastes related to the barley variety or the malting process? As you would expect, the answer is “both,” and I learned why as Matt Letki walked me through the process. I had hoped to get that post prepped before I headed off to Prague, but it will probably not be ready until I return after February 15th. Teaser: a big part of the answer has to do with the phrase “biochemical levers.” Fun stuff; stay tuned.

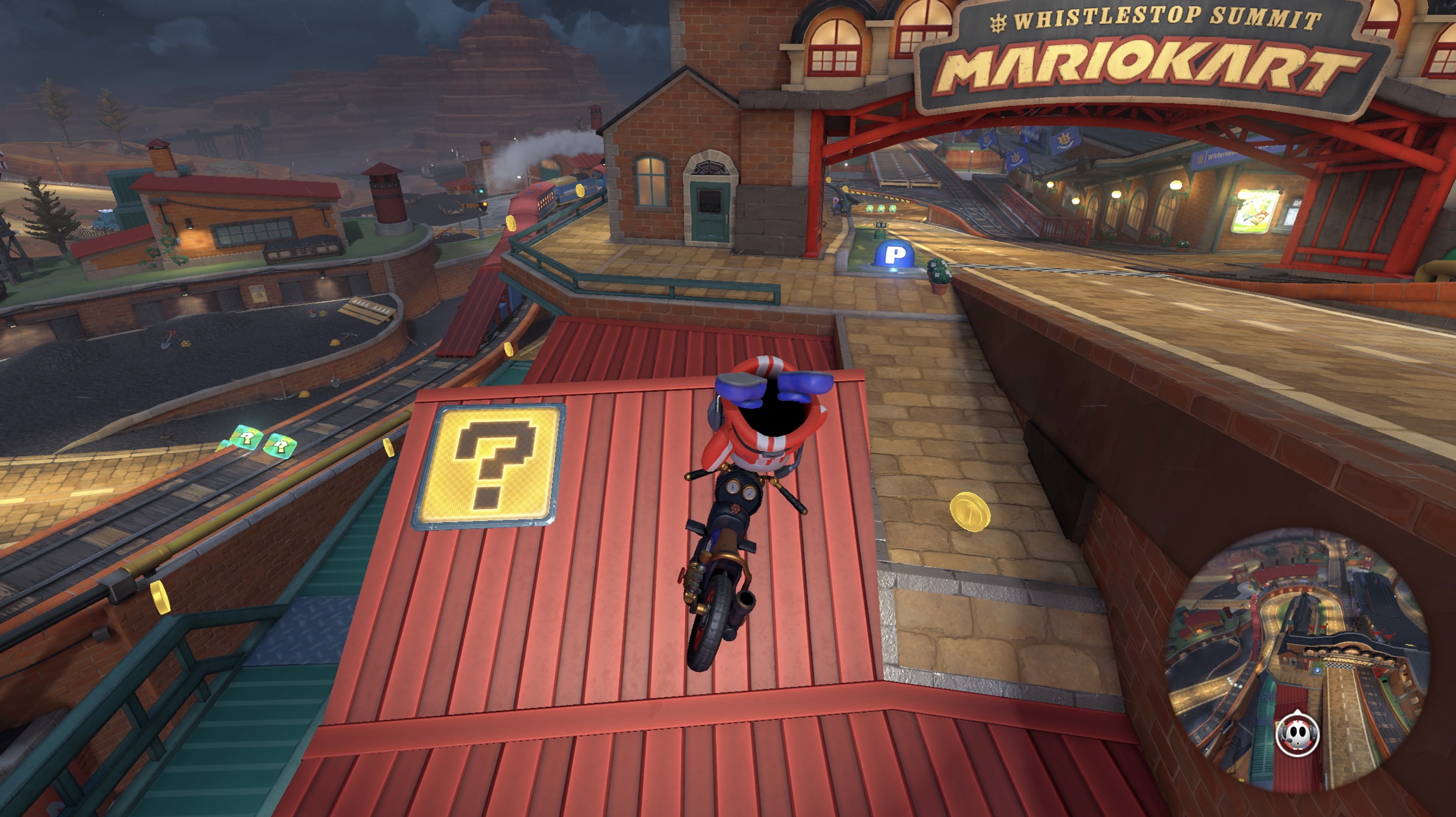

The real game takes place in the spaces between those race courses.

Credit:

Nintendo

The real game takes place in the spaces between those race courses.

Credit:

Nintendo

Any resemblance to the <em>Mad Max</em> film franchise is completely coincidental.

Credit:

Kyle Orland

Any resemblance to the <em>Mad Max</em> film franchise is completely coincidental.

Credit:

Kyle Orland

Not all of the collectibles are especially well-hidden...

Credit:

Nintendo

Not all of the collectibles are especially well-hidden...

Credit:

Nintendo

Stay on target...

Credit:

Nintendo

Stay on target...

Credit:

Nintendo